The Regulator Who Cried Wolf: Why is the PCAOB Citing the Same Standards Year After Year After Year?

As children, we all heard the story of the boy who cried wolf. Leaving the sheep and wolves aside, what happens when the audit regulator continues to cite the same auditing standards year after year in its firm inspection reports? Does the PCAOB’s message lose its effectiveness? Does the public become like the townspeople who eventually stop listening or responding?

Did you know that there are currently over 50 auditing standards that have been issued by the PCAOB? 55 to be precise. On top of that there are other various rules over ethics and independence, quality control standards, and attestation standards. Some of the auditing standards are only five paragraphs, such as AS 1010 – Training and the Proficiency of the Independent Auditor while other standards are 98 paragraphs long with as many as three appendices such as AS 2201 – An Audit of Internal Control Over Financial Reporting That is Integrated with An Audit of Financial Statements.

Wow. That’s a lot of guidance and presents so many opportunities for audit deficiencies. And yet, surprisingly, the PCAOB seems to take issue with many of the same auditing standards year after year after year.

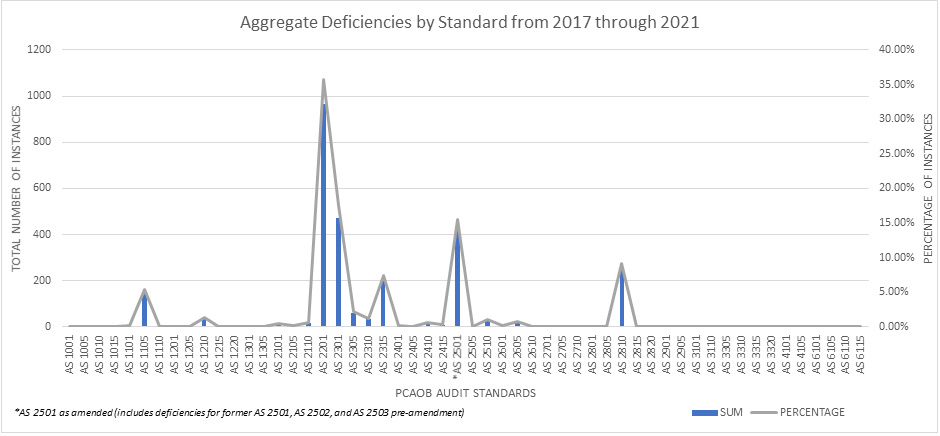

After analyzing the PCAOB’s common findings, we decided to perform our own analysis of PCAOB inspection reports to evaluate the evolution of those reports over time and the nature of the findings described by the PCAOB. Perhaps not surprising, we found many of the same themes that the PCAOB self-reported. However, what was surprising is that approximately 77.8% of the PCAOB’s findings can be boiled down to just a couple auditing standards (AS 2201, AS 2301, AS 2501, AS 2810) and within those standards, the PCAOB seems to generally cite just a couple paragraphs. Add in two more standards (AS 1105 and AS 2315) and you have now accounted for approximately 90.6% of all deficiencies.

The Process

To start, we began by analyzing the general evolution of firm inspection reports. Understandably, early on in its formation, the PCAOB was growing and adapting as it learned what it meant to be an audit regulator. The early reports morphed almost every year. Earlier reports were organized by issue while later reports came to be organized by issuer. Sometimes the reports varied between the detail for Big Four and those for the small and mid-tier firms. Early on, there was no specific citation of auditing standards. In fact, auditing standards were not specifically referenced in the public reports until 2014.

The PCAOB continued to modify reports over time and then with the entirely new Board appointed in 2018, the entire report changed. The inspection reports became more uniform, more condensed, and provided some context for readers to understand how to interpret the results, such as historical inspection results so that readers could understand quality trends.

To do our analysis specifically, we took the information from all domestic inspection reports published from 2017 (after the PCAOB codified the old standards) through July 7, 2021. In Part 1 of the inspection reports, we then counted each time an auditing standard was cited (one reference to a standard equates to one deficiency, regardless of the number of paragraphs referenced). Then we began to aggregate and analyze the data.

The Findings

Let’s take a closer look at the findings and what they indicate:

AS 2201 An Audit of Internal Control Over Financial Reporting That Is Integrated with An Audit of Financial Statement (35.8%)

Surprise, surprise. Deficiencies in testing over internal controls have been a challenge since the onset of Sarbanes-Oxley. Over the last couple years, there seem to be more and more concerns related to auditor’s testing over management review controls (MRCs), but this has been the case since 2013 when the PCAOB released SAPA 11 with specific guidance over MRCs. Yet, teams continue to struggle with identifying controls to address relevant assertions, testing completeness and accuracy over information used in controls, and sufficiently testing the design and operating effectiveness of controls. What this means is that in almost 20 years since the onset of SOX, the industry still struggles to “get it right.”

AS 2301 The Auditor’s Responses to Risks of Material Misstatement (17.5%)

The PCAOB references a number of different paragraphs within this standard, but the general issue boils down to the fact that engagement teams fail to design and execute procedures sufficient to address the risk of material misstatement. Some of the guidance is very prescriptive; for instance, for significant and/or fraud risks, auditors must perform a test of detail (no exceptions). For all relevant assertions, engagement teams must perform substantive procedures (no exceptions). However, the overall design of the audit is inherently based on risk. Applying significant, professional, auditor judgment, engagement teams must determine the nature, timing and extent of testing to be performed, taking into account both controls and substantive procedures. The PCAOB’s findings with respect to AS 2301 calls into question the auditor’s ability to apply judgment and effectively design audits to address the risks of material misstatement. Considering how foundational risk assessment is to the overall execution of the audit, this finding carries a lot of weight.

AS 2501 Auditing Accounting Estimates, Including Fair Value Measurements (15.5%)

Again, no surprise here. The continued findings involving estimates is perhaps what spurred the PCAOB to issue new guidance in a revised AS 2501 standard. But let’s be honest, that standard didn’t really change the guidance significantly. It really condensed AS 2501, AS 2502 and AS 2503 into one main standard, but the meat and bones of the audit procedures expected to test management estimates did not drastically change. Despite the continued focus over auditing estimates, firms across the industry are failing to sufficiently audit these areas.

AS2810 Evaluating Audit Results (9.0%)

Scanning through our findings, the deficiencies related to AS 2810 tended to fall into two main areas. First, engagement teams failed to sufficiently consider contradictory evidence. This means that teams did not sufficiently document or dispose of information that might have contradicted management assertions or engagement team conclusions. Second, auditors failed to perform sufficient procedures to conclude on specific accounting considerations and whether financial statements were appropriately presented. Both of these findings are alarming considering audits are designed to act as a check on management. So, to think that auditors are not considering contradictory evidence would inherently call into question the purpose of an audit. In addition, audits are designed to ensure that the financial statements are fairly stated (including presentation and disclosure, which is predicated on accounting considerations). So, to think that auditors are failing to sufficiently audit accounting considerations, again, makes us wonder, what is the audit actually accomplishing?

Other Considerations

As the table shows, there were, of course, other audit areas that are cited. And this is certainly not a complete picture of the PCAOB’s findings. This analysis represents only Part I findings, or in other words, findings that mean the auditor’s opinion is not supported. For instance, a PCAOB comment over audit committee communications would not necessarily jeopardize the audit opinion and so these types of comments have traditionally only been disclosed in Part II of inspection reports, which are private, unless a firm fails to pass remediation. Only recently with the new report format, Part I B discloses some of these findings. As well, this analysis does not take into account clean inspection reports where no Part I issues were identified.

It is worth noting however, of all inspection reports published from 2017 to 2021 (to-date) approximately 58% of firms have at least one deficient audit. That means more than half of the industry is failing in the eyes of the PCAOB. Whoa!

So What Does it All Mean?

Taking a step back, what does the data mean or suggest? For us, it raises several questions:

- Does the PCAOB have a moving target?

While the PCAOB has issued new auditing standards, the standards cited above have not significantly changed in the last five years. And yet, despite the lack of significant changes, firms still seem to be missing the mark. In our work supporting firms, time and again we’ve heard engagement teams defend their work, saying, “Well, the PCAOB was okay with this during the last inspection,” only to then get a comment this year on the most recent inspection. This begs the question, does the PCAOB have a moving target? Why is it that management review controls became a hot topic in 2013 and has since yet to be resolved? Were firms sufficiently testing MRC’s prior to 2013 and then suddenly the industry shifted? Realistically, no. Rather, the PCAOB refined its knowledge and understanding and interpretation of the guidance and started issuing comments over MRCs where teams only checked for sign-off. Call a spade a spade; that’s essentially a moving target. We aren’t saying that the PCAOB can’t evolve and refine guidance and/or interpretations, but it also makes it hard to satisfy PCAOB expectations when the bar keeps apparently shifting.

- Are the PCAOB’s expectations unattainable?

Perhaps the PCAOB’s expectations are not a moving target. But are they achievable? Audits are predicated on the concept of “reasonable assurance.” What does that actually mean? When an estimate is inherently uncertain and unable to be justified with exactitude, what is defined as reasonable assurance? Despite the recurring nature of these findings, firms are struggling to meet expectations. At a certain point, the regulator has to wonder, are we being reasonable?

- How effective is the PCAOB remediation process?

As part of the PCAOB inspection process, firms have one year to remediate issues identified in Part II of the report. Part II includes quality control criticisms that are derived from the Part I findings. Most firms pass remediation, meaning the PCAOB believes the actions undertaken by the firms are sufficient to remediate the potential quality control issues present at the firm, such that they should address the inspection findings. Despite the fact that most firms pass remediation, if we’re seeing the same issues in inspection reports year over year, what does that actually say about the remediation process? Is it actually effective? Do firms understand the root cause of the issues? If a firm fails to remediate the QC criticisms, the PCAOB will release those Part II criticisms to the public. For context, this has happened a handful of times for various firms; for one of the Big Four firms, out of the 17 inspection reports published for the US firm, the PCOAB has released portions of the Part II report only twice. Is the threat of releasing Part II sufficient to encourage firms to effectively remediate issues? And is the remediation process actually working if we’re still seeing the same issues surface across the industry year after year?

- Is the PCAOB doing enough to provide relevant guidance?

When the industry continually fails to achieve expectations, it is incumbent upon the regulator to understand why. Should the PCAOB be providing more guidance to help firms improve quality and better understand expectations. On inspections, the PCAOB currently focuses on identifying the issues, but does not provide guidance on how to fix them. Even the comment forms issued after an inspection read as a “failure” without providing guidance on what could be done to improve the testing or to avoid the issue. While we realize there is no “one way” to perform an audit, perhaps in addition to identifying the failures, the PCAOB could start to offer solutions such as “here’s what you could do.” In fact, for many of us at JGA, this is what prompted us to leave the PCAOB. We got tired of merely pointing out the problem without providing solutions. Maybe it is time the PCAOB put itself in the shoes of the firms and offer guidance on what firms could have done differently to overcome the issues.

- What will it take for the industry to finally achieve audit quality in the eyes of the PCAOB?

We would be remiss to point all fingers at the PCAOB without taking some responsibility as an industry. In our role supporting firms, there are those engagement teams that put a lot of effort and barely miss the mark; when the PCAOB issues comments in these situations, it makes us wonder about “moving targets” or “unattainable expectations.” But let it also be known, there are situations where audit firms grossly miss the mark and these are the situations for which PCAOB inspections were designed; to identify audit quality concerns. These situations are where firms need to take a serious look at “what went wrong?” and take ownership over the fact that there were quality control issues. Perhaps firms need to revisit staffing and ensure jobs have the appropriate resources, both in terms of number of staff, knowledge of staff, and time allocated for engagements. Perhaps firms need to provide additional guidance, tools and templates to their staff to help enable effective quality audits. This is exactly what the remediation process is designed to do. Maybe this is a wake-up call for firms to commit more resources to ensuring all audits are performed in a quality manner.

Not only is it the same deficiencies, but looking at reports published from 2017 through 2020, there are more and more deficiencies being cited per inspection report. That’s not a positive trend. We think the industry overall would agree that the PCAOB has brought about significant change and audit quality has improved from the turn of the century. But have we reached a plateau? What will it take to tackle these recurring issues? And is the PCAOB merely crying wolf in citing the same standards year over year over year without taking action to effectuate change? Give it enough time and people stop listening when it’s the same message and there’s no change. What will happen then when the PCAOB finally spots an actual wolf and identifies a truly egregious audit issue?

Dane Dowell, CPA

is

a Director at Johnson Global Accountancy who works with PCAOB-registered accounting firms to help them identify, develop, and implement opportunities to improve audit quality. With over 12 years of public accounting experience, he spent nearly half of his career at the PCAOB where he conducted inspections of audits and quality control. Dowell has extensive experience in audits of ICFR and has worked closely with attorneys in the PCAOB’s Division of Enforcement and Investigations. Prior to the PCAOB, he worked with asset management clients at PwC in Denver, Singapore, and Washington, DC.

Joe Lynch, JGA Shareholder, to Provide Insights on Changes to Engagement Quality Review Requirements